About The House of Nobel Laureate Ivo Andric

Living room

The house of the Nobel laureate Ivo Andrić was revitalized in the period 2018-2020. by the efforts of the Municipality of Herceg Novi, with

special support from institutions and individuals:

Office of the President of the Municipality of Herceg Novi

Office for International Cooperation of the Municipality of Herceg Novi

Agency for the construction of Herceg Novi

Tourist organization Herceg Novi

Secretariat for Culture and Education of the Municipality of Herceg Novi

JU “Mirko Komnenović City Museum and Josip Bepo Benković Gallery”

JUK “Herceg Fest”

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Serbia

Consulate of the Republic of Serbia in Herceg Novi

Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts

Belgrade City Museum

Memorial Museum of Ivo Andrić, Belgrade

Endowment of Ivo Andrić, Belgrade

The project was financially supported by the European Union within the framework of the IPA project “Co. Co. Tour” with the help of the Agency for local democracy from Nikšić.

The expert team for the revitalization of the House of Nobel laureate Ivo Andrić:

PhD Vladimir Roganović

Tatjana Korićanac

PhD. Dragan Bulatović

Dimitrije Vujadinović

Bojana Đurović

Aleksandar Pribićević

Reklame Svijet

PATHS

In the spring and summer of 1961, Andrić and his wife Milica Babić spent several months in Herceg Novi, in the hotel “Boka”. Their oasis was apartment number 10, and the trails in Herceg Novi led them through the park “Boke”, the “Pet Danica” promenade, the Old Town and the city hinterland. The paths led to the churches of Herzeg Novi, fortresses, gardens, bays, mandraci, beaches. These are Andrić’s trails in Nov. Sunny paths…

When we were thinking about where we could build holiday houses on the sea, Milica and I easily agreed decided on the Bay of Kotor. The sun attracted us the most.

Whenever I found myself down there, I would remember her

Bosnian proverbs: In the sun there are seven berries, and in the rain only one!

Somewhere halfway between the “Boka” park and the churches of Saint George and Saint Savior, where Njegoš studied lettered by hieromonk Josif Tropović, this house was built in 1963. Classy in its modesty, harmonious has merged with the greenery of the garden, which is bordered on three sides by narrow streets.

Always is sunny and pleasantly shady. And everything on the house and around it is arranged so that there is nothing to worry about

add nor subtract.

The house is close enough and far enough to everything: the coast, the sun and – silence.

As if it had always been there: The house of Nobel laureate Ivo Andrić, in Njegoševa Street.

I could not remember any, even a short period in my life without Njegoš’s verse, without thoughts of Njegoš.

LANDSCAPES

From the terrace of Andrić’s house, on a bright and calm morning, which can dawn in Novome more often than elsewhere, the view through palm trees and cypresses, across the Boko Kotor amphitheater, reaches as far as it can go to Lovcen himself.

When I sit in front of the house, I have a view in front of me that looks like it was chosen by a nature lover beauty and not a game of chance. I see the wide opening of the Boke and a sharp edge along its entire length the sea, like a taut rope of dark sapphire color, from Cape Luštica to Punta Oštra, on which my imagination thanks to his invisible and silent games and tricks.

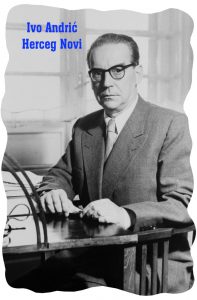

The house was built in 1963 by Ivo Andrić (1892-1975), winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature (1961).

The writer often stayed and created in the house from 1963 to 1968.

Andrić started visiting Herceg Novi at the end of the 1950s, usually with his wife

Milicom Babić Andrić (1909-1968). In Herceg Novi, a city with a special aura, the writer found

an environment that ennobles the idea, sharpens the thought and strengthens the noble intention.

Andrić decided that precisely in Herceg Novi, on Topla – which is as dear as an unusual female name, and in it, so small, is hidden all the life of the world, past, present and future – build the only house for his life. The project was entrusted to the distinguished Belgrade architect and painter Vojislav Đokić, who is himself often stayed in Herceg Novi.

The house and the garden witnessed the emergence of many creative formulas. They encouraged Andrić to go full circle his poetics and literary-philosophical thoughts, which were translated into the all-time Signs by the Road, as well as Omerpasha Latas unfinished novel and some of writers later short stories.

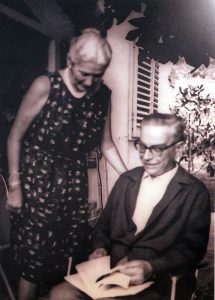

In Andrić’s house, the faces of his world are reflected. The special face of his wife, Milica Babić (1909-1968). “Smart and good in everything”, the first Serbian trained costume designer incorporated her with the writer refined taste in every detail of the home of love. In one of Andrić’s letters to Milica in Herceg Novi sent from Bled, he writes to her: I am thinking about you and home […] This is how when I am far away among other people everything the worries and difficulties there seem smaller, and our house is paradise.

Color room

It was nice for me in Herceg Novi. On clear days, from the balcony of my house I often looked and thought about

to the Montenegrin bishop Njegos. The Venetians, Turks, Spaniards, Russians, Austrians fought over the Bay of Kotorska… No matter what

would about such beauty!

HOUSE WITH A VIEW

Everything I saw in my childhood – people, things and places – all this could never satisfy my thirst for beauty and perfection. Everything I saw around me I constantly imagined in another, more beautiful and more perfect form, and I believed that it really existed, but somewhere far away. Then a desire arose in me to go on a journey to those distant countries and to see that more beautiful and perfect life. And off I went.

I am sitting on a green bench that has sunk into the lush vegetation. I don’t know the exact name of the end where this flows my afternoon. I don’t find anything definite and reliable in my thoughts about myself either memories. I did, and I’m here. This is all. I could not determine the sides of the world exactly. I just feel that somewhere the sun is setting, but I don’t know that there are landscapes beyond the ones I see. I only know that life, when it already exists, must be eternal, and I lose myself in that knowledge.

When it’s a rainy summer, the whole world complains. Vegetable sellers, hoteliers and farmers complain, rightly so. They complain

citizens and gentlemen, because their vacation was spoiled. But, have you noticed how flowers are for a rainy person summer? Larger, more beautiful and brighter in color and shape, especially in color. I see him as a silent glory.

Andric’s garden is the place where the feelings of the owners of the house clashed most aesthetically. Rich, fresh,

colorful, inspiring. In his notebooks, Andrić writes that 51 different flora species grew in it, that there were “about 12 types of vegetables” in the small vegetable garden. Andrić is generous with the assets of that environment used, just like all the inhabitants of the cities on the sea coast.

1) On the seashore, thought is slower, it occurs less often, but that is why it is finer and sharper when it occurs.

2) Only the element of the sea can be compared to the element of snow.

3) By the sea, it seems, there are no flowers without fragrance.

STAIRS AND HALLWAY UPSTAIRS

There were so many things in life that we were afraid of. And it shouldn’t have been. It was meant to be lived.

During Andrić’s stay, the house was also a kind of Herzegovinian art salon. Andric and Milica Babic are here was visited by artists and personalities who modeled the cultural and artistic climate of the city, but also South Slavic and European areas: Branko Ćopić, Mihailo Lalić, Zuko Džumhur, Branko Lazarević,

Desanka Maksimović, Stevan Raičković, Dušan Kostić, Gun Bergman, Ilja Erenburg, Novljani Vojo Stanić, Bosiljka and Ilija Pušić, Luka Tomanović and many others.

This coastal city has attracted artists since ancient times: there was once, albeit in exile,

the Portuguese poet Didako Piro stayed there, Evlija Celebija also traveled there, and he lived there for a while Pierre Loti, and Vuk, Njegoš, Matavulj, Šantić, Nušić and so many others visited… Even today, many artists they stop in Novi, some live there, like Mihailo Lalić or spend several months like Dušan Kostić, Stevan

Raičković, painter Vojo Stanić […] Even Njegoš could not remain indifferent to such beauty,

so sang: Novi Grad, you are sitting at the end of the sea, and you count the waves down the open sea…

While reading Don Quixote in the original, I find more than when reading any other classical writer encouragement, encouragement and strength to be who I am in my literary work and in my actions.

Art is also similar to life: it looks like a game, and in fact it is a devilishly serious matter; and all the more serious if it’s more like a game.

I learned very early that every minute of life, it can be as difficult as life as a whole.

Today, even the visitor to Andrić’s house is invited to embark on his own journey through the landscapes that are watched by our Nobel laureate. It is called and inspired by places from the imagination to which you can go from the garden, the study, from the terrace, etc …

Ivo Andrić also pointed meditatively from the balcony of this house. And that scene invites the observer into his world own games played by the visitor himself.

It is an illuminated, miraculous showcase, made up of the boundless expanse of the sea and the cloudless serenity of the sky and waves, with no ship in sight. It is a bright desert and a void rich in all possibilities.

And for me, there are unexpected changes and incredible scenes that only I can see and over which impermanence has no power, because they are born and die at the same moment, so that between their origin and disappearance there is not even the smallest gap and that time cannot insert its destructive germ between them. They also appear they disappear in one and the same flash; they do not last, and they are eternal, because they change forever and thus are not subject to transience.

“AND HOW I BECAME A WRITER”

In 1912, Andrić left Višegrad and enrolled in the Great Gymnasium in Sarajevo. In school lessons he recites verses by Heine and Goethe by heart, reads Don Quixote in a German translation, rapidly progressing to learning that language which, many years later, will elite rule his personal library.

Andric’s first strong memory related to books originates from that time: “On rainy afternoons, when boys my age yearn for something new, beautiful and exciting, they look for food for the soul and imagination, food that they need as much as bread and water, and that in our times neither house nor school nor society could provide, I often left our cheerless room and stare through the alleys, along the uneven large cobblestones, went down to a flat and beautiful part of the city. I went straight to the bookstore and stood for a long time in front of her window, which I knew so well that I noticed every little thing change and looked forward to it as a personal experience. I walked away from that shop window several times and then again returned, until the fall evening stops and until the light shines in the window, and its reflection falls on the wet asphalt. Then you had to leave all that and go back up in the mahal to your real life.

But the illuminated window display was not easy to forget. In boyish dreams and half-dreams at night, he shone and circled in fantastic transformations; it was no longer an ordinary city window with books, but a cosmic one light, a part of some constellation that I aspired to with great desire, but with the painful knowledge that it was mine unattainable.”

A LIFE WITH TWO BIOGRAPHIES

Andrić was born in 1892 in Doc near Travnik. After his father’s death, he moved to his aunt and uncle in Višegrad, where he finished elementary school, and then entered the Velika Gymnasium in Sarajevo. As a high school student, he shows talent for languages, translation, literature. Joins the revolutionary organization of pupils and students Mlada Bosnia, that after the assassination in Sarajevo, someone would then execute him because of his ideological affiliation time in prison.

He began his studies at the Faculty of Arts in Zagreb, and continued them in Vienna and Krakow, in order to interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War by force of circumstances. He will only graduate in 1924 in Graz, in the field of history of Austria, philosophical sciences and Slavic philology, which fulfills the condition necessary to stay in diplomatic service. He entered it in 1920, after deciding to permanently move from Zagreb to Belgrade, where he lives settle down. Embassy of the Kingdom of H.S.H. pri is Andrić’s first destination. Since then, until 1941 when is retired, building a career as a diplomat of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

After the end of the war, he was the president of the Union of Writers of Yugoslavia, socially and politically engaged in The Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Federal Assembly. He traveled with cultural, literary and educational delegations of the country abroad and wrote.

Until his death in 1975, he lived and worked in Belgrade. He was buried in the Alley of the Great at the New Cemetery.

He began as a poet by publishing two collections of lyrical prose, Ex Ponto and Nemiri, and the short story “The Way of Alijah

Đerzeleza” which is at the root of his future narrative prose. In Zagreb they wrote about him then:

“Unhappy like all artists. Ambitious. Sensitive. In short: it has a future.”

In the interwar period, he was mainly devoted to short stories and novellas, some of which are included in top European achievements in the narrative genre. Immediately after World War II,

published three novels-chronicles in a row: Na Drina ćuprija, Travnička hronika and Gospodjica, and in 1954 the novel Prekleta avlija.

In 1961, he became the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, which he received at a traditional ceremony in Stockholm on December 10.th three more books by Andrić were published posthumously: Roadside Signs, Omerpaša Latas, unfinished a novelist’s venture, and a collection of stories The Lonely House. In addition to his literary manuscripts, he also left brilliant essays on Njegoš, Vuk Karadzic, Petrarch, Goya, Bolivar, and he was also a great literary critic.

DIPLOMATIC YEARS

In 1919, Ivo Andrić moved from Zagreb to Belgrade, the capital of the newly created State of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, then the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In 1920, he entered the service of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which begins his twenty-year-long and successful diplomatic career, which ends with an outbreak of the Second World War.

During many transfers and appointments, he advances in titles and describes the increasingly complex diplomatic circle in career – Rome, Vatican, Bucharest, Trieste, Graz, Marseille, Paris, Madrid, Brussels, Geneva, Belgrade, Berlin. Already as a young diplomat he spoke, read and wrote several foreign languages, which enabled him to European capitals and their history, art, literature, philosophy, learns from the original, from authentic writings.

Erudite, an intellectual educated on the best of the European cultural and artistic heritage, brilliant

a storyteller, a thinker, a connoisseur of history, philosophy, poetry, art, a gentleman in manners and

manners, Andrić has outgrown his official diplomatic career and his literary legacy.

In constant fear for survival “because there is nothing permanent or certain in that service”, Andrić will make adjustments in which, from year to year, there will be less and less resistance and more and more reconciliation with things, in which lose the marks of his early rebellious nature.

In his work, according to the judgment of some contemporaries, “cautious, fickle, dishonest”, an exemplary student Machiavelli and Guicardini, who will serve as a model for him in understanding the mechanism of history, but also for instruction in performing the work he was engaged in, for which, as he says, it is necessary to have a cold and good one mind.

Nevertheless, Andrić will reveal that in his desire to “please God without resenting the devil” he made many compromises that he will transfer to himself, and according to his own admission, he will also leave a few feathers to whomever he likes never mind

I LEFT

I left behind everything people said,

like a wisp of mist that disappears.

And everything they did, I carried in the palm of one hand.

Ivo Andric

STOCKHOLM

DECEMBER 10, 1961

ABOUT STORY AND TALKING

…In a thousand different languages, in the most diverse living conditions, from century to century, from the ancient patriarchal ones stories in huts, by the fire, all the way to the works of modern storytellers who are coming out at this moment from publishing houses in major world centers, the story of man’s destiny is being told, which has no end and interrupts people talking to people. The way and forms of that talk change with time and circumstances, but the need he stays behind the story and talking, and the story continues and there is no end to the talking. That’s how it sometimes seems to us humanity, from the first flash of consciousness, throughout the centuries talks only about itself, in a million variants, alongside with the breath of his lungs and the rhythm of his bila, the same story over and over again.

And that story seems to want to, like talking of the legendary Scheherazade, to deceive the executioner, to delay the inevitability of the tragic fate that threatens us, and extend the illusion of life and duration. Or maybe the storyteller with his work should help the man to find himself power? Perhaps it is his call to speak on behalf of all those who were not able to, or were shot down before their time life-blood, they didn’t have time to express themselves? Or maybe the narrator is telling his story to himself, like a child who it sings in the dark to deceive its fear?…

Perhaps the true history of humanity is contained in those stories, oral and written, and perhaps from they could at least guess, if not find out, the meaning of that history…

But it is permissible, I think, in the end to want to tell the story that today’s storyteller tells his people time, regardless of its form and its theme, is neither poisoned by hatred nor drowned out by thunder of murderous weapons, than is possible more driven by love and guided by the breadth and cheerfulness of the free of the human spirit. Because the storyteller and his work are of no use if they do not serve in one way or another to man and humanity. That’s what matters.

Fragment of Andrić’s solemn speech

December 10, 1961, Stockholm

The bridge on the Drina River, next to which Anrdrić grew up in Visegrad, became the backbone and main character of his of the novel Na Drina ćuprija (1945), the pivot of the epic opus for which Andrić received the Nobel Prize in 1961 award. The eleven-arched stone bridge was built by Grand Vizier Mehmed Pasha Sokolović in the 16th century as his endowment, in the homeland from which he was taken as a child according to the custom of taking a “tribute in blood”.

He was turned into a Turk, and then over the years he managed to climb the ladder of power as the first to the sultan.

The bridge is a unique symbol of the Romanesque narrative that follows the life of the Visegrad kasaba on its banks through centuries, shifts and changes, shifts of government and military units, times of rise and times of suffering, indicating the transience and decay of human life that only a magnificent stone bridge could give survive. Andrić’s epic story about the past of Bosnia in “Turkish times”, along with the Travnička novels chronicle and Omerpaša Latas, rounded off the chronicle, which with its literary, aesthetic and ethical values and is still searching for answers about the destiny and meaning of man’s existence on earth.